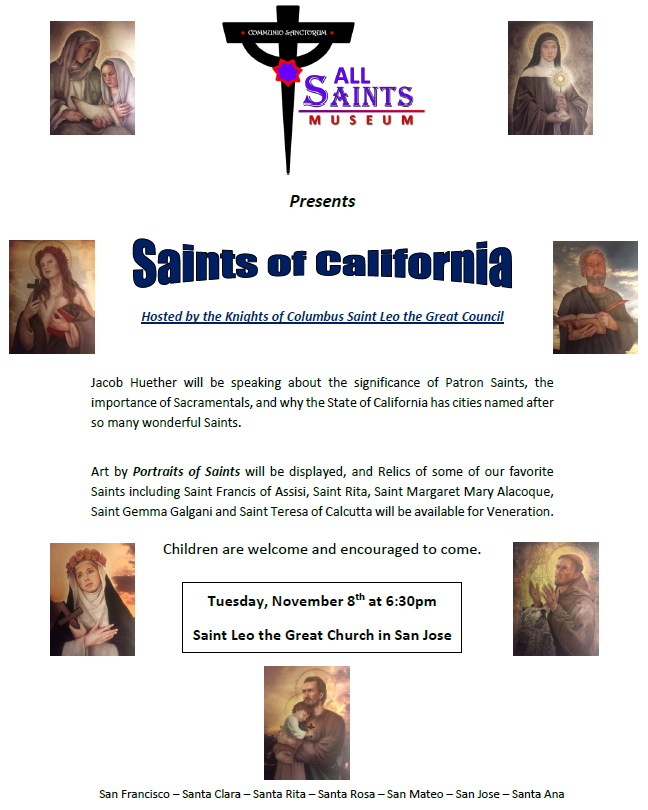

Come listen to Jacob Huether, founder of All Saints Museum, give a talk on the Saints of California.

Category: Sacraments

History of the Sign of the Cross

I recieved this in an email from a good friend and wanted to pass it along.

The Sign of the Cross

- FR. WILLIAM SAUNDERS

My friend is Greek Orthodox. In his Church, they make the sign of the cross crossing themselves from the right shoulder to the left, but we do the opposite. Why is there a difference? When did this come into practice?

|

|

The sign of the cross is a beautiful gesture which reminds the faithful of the cross of salvation while invoking the Holy Trinity. Technically, the sign of the cross is a sacramental, a sacred sign instituted by the Church which prepares a person to receive grace and which sanctifies a moment or circumstance. Along this thought, this gesture has been used since the earliest times of the Church to begin and to conclude prayer and the Mass.

The early Church Fathers attested to the use of the sign of the cross. Tertullian (d. ca. 250) described the commonness of the sign of the cross: “In all our travels and movements, in all our coming in and going out, in putting on our shoes, at the bath, at the table, in lighting our candles, in lying down, in sitting down, whatever employment occupies us, we mark our foreheads with the sign of the cross” (De corona, 30).

St. Cyril of Jerusalem (d. 386) in his Catechetical Lectures stated, “Let us then not be ashamed to confess the Crucified. Be the cross our seal, made with boldness by our fingers on our brow and in everything; over the bread we eat and the cups we drink, in our comings and in our goings out; before our sleep, when we lie down and when we awake; when we are traveling, and when we are at rest” (Catecheses, 13). Gradually, the sign of the cross was incorporated in different acts of the Mass, such as the three-fold signing of the forehead, lips, and heart at the reading of the gospel or the blessing and signing of the bread and wine to be offered occurs about the ninth century.

The earliest formalized way of making the sign of the cross appeared about the 400s, during the Monophysite heresy which denied the two natures in the divine person of Christ and thereby the unity of the Holy Trinity. The sign of the cross was made from forehead to chest, and then from right shoulder to left shoulder with the right hand. The thumb, forefinger, and middle fingers were held together to symbolize the Holy Trinity — Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. Moreover, these fingers were held in such a way that they represented the Greek abbreviation I X C (Iesus Christus Soter, Jesus Christ Savior): the straight forefinger representing the I; the middle finger crossed with the thumb, the X; and the bent middle finger, the C. The ring finger and “pinky” finger were bent downward against the palm, and symbolize the unity of the human nature and divine nature, and the human will and divine will in the person of Christ. This practice was universal for the whole Church until about the twelfth century, but continues to be the practice for the Eastern Rites of the Catholic Church and the Orthodox Churches.

An instruction of Pope Innocent III (1198-1216) evidences the traditional practice but also indicates a shift in the Latin Rite practice of the Catholic Church: “The sign of the cross is made with three fingers, because the signing is done together with the invocation of the Trinity … This is how it is done: from above to below, and from the right to the left, because Christ descended from the heavens to the earth, and from the Jews (right) He passed to the Gentiles (left).” While noting the custom of making the cross from the right to the left shoulder was for both the western and eastern Churches, Pope Innocent continued, “Others, however, make the sign of the cross from the left to the right, because from misery (left) we must cross over to glory (right), just as Christ crossed over from death to life, and from Hades to Paradise. [Some priests] do it this way so that they and the people will be signing themselves in the same way. You can easily verify this — picture the priest facing the people for the blessing — when we make the sign of the cross over the people, it is from left to right….” Therefore, about this time, the faithful began to imitate the priest imparting the blessing, going from the left shoulder to the right shoulder with an open hand. Eventually, this practice became the custom for the Western Church.

In the classic work, The Ceremonies of the Roman Rite by Adrian Fortescue and J. B. O’Connell, the sign of the cross is made as follows: “Place the left hand extended under the breast. Hold the right hand extended also. At the word Patris [Father] raise it and touch the forehead; at Filii [Son] touch the breast at a sufficient distance down, but above the left hand; at Spiritus Sancti [Holy Spirit] touch the left and right shoulders; at Amen join the hands if they are to be joined.” Although this practice may have evolved from the original and still current practice of Eastern Rite, it nevertheless has been the standing custom for the Latin Rite Church for centuries.

No matter how one technically makes the sign of the cross, the gesture should be made consciously and devoutly. The individual must be mindful of the Holy Trinity, that central dogma that makes Christians “Christians.” Also, the individual must remember that the cross is the sign of our salvation: Jesus Christ, true God who became true man, offered the perfect sacrifice for our redemption from sin on the altar of the cross. This simple yet profound act makes each person mindful of the great love of God for us, a love that is stronger than death and promises everlasting life. The sign of the cross should be made with purpose and precision, not hastily or carelessly.

Catholic Museums

There is a real need for Catholic Museums, not just in our local areas, but in the world.

The quintessential Catholic “family outing” is the Sunday Mass. And this is critical – the Eucharist is the source and summit of our Faith.

But outside of the Mass there are very few Catholic activities designed for, or that appeal to, the family. I think that there is more that needs to be done to spark an interest in the Faith.

If we can draw a parallel, I think we can compare the Faith Life to a fire. You need 3 things, fuel, oxygen and heat. The Mass (and all the Sacraments) are like the fuel. They keep our Faith alive by Divine Grace. But we also need good Catechesis / education – the Oxygen, and we also need personal desire or inspiration – the heat.

You can have a Catholic that is educated and well formed, and receives the Sacraments, yet has little motivation or inspiration… they do the bare minimum, and therefore they are a flickering flame. You can also have a person who is Inspired and has great desire, and receives all the Sacraments, but hasn’t been well informed. Those inspirations and desire are short lived without a proper education and understanding. And likewise you can be well informed and have inspiration, but if you aren’t living the Sacramental Life then something is amiss.

A Catholic Museum helps to add elements of the Education and Inspiration back into our community. Together with the Sacraments, this can be a recipe for a renewed Faith Life!

I pray that All Saints Museum contribute to this.

Marriage and Faith

Faith is “the substance of things hoped for, the evidence of things that are unseen.” (Heb 11:1).

This is not the dictionary definition of faith, but an inspired one from the Holy Spirit, who inspires the Scriptures. This Faith is a gift from God himself – the first of the three Theological Virtues (Faith, Hope and Love) – given to us through grace.

Our Lord has revealed to His Church that the ordinary means of obtaining grace is through the Sacraments!

The Catechism of the Catholic Church states: “The purpose of the sacraments is to sanctify men, to build up the Body of Christ and, finally, to give worship to God. Because they are signs they also instruct. They not only presuppose faith, but by words and objects they also nourish, strengthen, and express it. That is why they are called ‘sacraments of faith.’“

We are given the initial bud of grace, Divine Life, when we are baptized. And this is when our parents make the ultimate act of Faith for us.

As we grow older, we have the Sacraments of Confession and Holy Communion to keep this Divine Life within us growing – and it is in this Divine Life that we continue to have Faith. And finally, the Sacrament of Marriage then strengthens this further. Marriage itself is the sign of God’s relationship with His Church, as St. Paul counsels the Ephesians when he says, “Husbands love your wives, even as Christ loved the Church (Eph. 5:25).” The family, stemming from Marriage, is a reflection of the Trinity, creating life through love. The family is evidence of the Triune God, who “is not seen” – except, of course, through Jesus, who is THE Sacrament Himself: “When you see me, you see the Father” (Jn. 14:9).

Marriage and the family then are very sacred entities, because as we live Sacramental lives, we may indeed give others a glimpse of what Faith is. We give others “evidence” of something unseen. We become the “substance of things hoped for” for others.

It is for this reason that we must always fight to defend Marriage, to defend the family. And the best way to do this is by imitating the Saints.

May we, through the veneration of the Saints of the past, inspire Saints of the future.

God bless.